The UK OASI Care Bundle: the results are out but so is the jury

Gill Moncrieff Research Fellow/Midwife, University of Central Lancashire UK

Hannah Dahlen Professor of Midwifery, Western Sydney University Australia

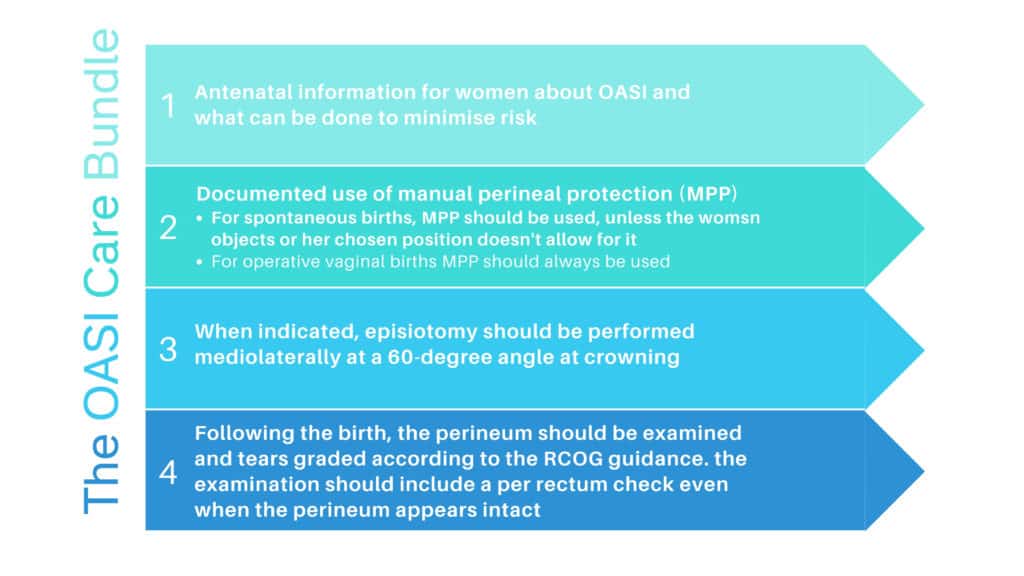

In 2014 the UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), and the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) responded to a reported rise in the rate of severe (3rd and 4th degree) severe perineal trauma (SPT)1 by recommending a Care Bundle with four main elements:

- antenatal information

- manual perineal protection for all vaginal births

- episiotomy with a 60° mediolateral angle at crowning when clinically indicated

- perineal examination, including per rectum after vaginal birth for all women

1We will use the term severe perineal trauma (SPT) instead of OASI as women have told us during research they find this term disturbing.

This year the evaluation of the Care Bundle was published. Having been regular critics of this project for various reasons, most which still hold true, we will give credit where credit is due. The study design was rigorous and impressively done. It was a stepped wedge trial evaluating the Care Bundle which was aiming to reduce severe perineal trauma (SPT). The right processes were followed: registering the study and publishing the protocol and then adhering to these in the analysis. A total of 55 060 women who had vaginal births in 16 units in four regions across England, Scotland and Wales were included (79% spontaneous and 21% operative). There was a reduction of 0.3% in SPT (3.3%-3.0%). There was no evidence of the effect being different when they considered parity or mode of birth and interestingly the caesarean section and episiotomy rate seemed unaffected. Why p<0.01 was not used for significance with such a large sample size is curious but the debate about statistical significance and clinical significance still rages on. The bottom line is the researchers thought of most things and the statistical analysis was impressive. However, a beautifully done study still relies on the right input and not just the right process and output.

So, what does a 0.3% reduction in SPT in over 55 thousand women mean? It is slightly concerning the authors at one point describe this reduction as a 20% reduction (this is when you can smell political intent), but essentially it means 94 women in the study did not get a SPT, or for every 333 women who had the Care Bundle there was one less SPT (numbers needed to treat). How many millions of pounds were spent to get this 0.3% difference and was this worth it? We can find no detail on cost but anyone who has experienced this serious perineal injury may consider this well worth it. Millions of pounds may have also been saved on reduced litigation costs, not to mention reductions in women’s long-term morbidity. On the other hand studies have shown better results with reducing SPTs not using the elements in this bundle, but a more woman centred and physiological approach. No doubt the debate will go on.

How good is the evidence informing the Care Bundle?

While we are certainly not contending there is a real need to reduce and prevent SPTs, the underlying evidence base of this Care Bundle is very much in question, including the impetus for developing the bundle in the first place. Many papers published by the developers of the Care Bundle and various webpages related to it cite an increase in SPT rates as the instigating reason for its development.

“In 2014 the RCM and the RCOG decided that something needed to be done to address the increasing rates of OASI (obstetric anal sphincter injury)” (RCM/RCOG, 2019)

However, the original paper highlighting this increase stated that ‘increased recognition of tears’ was the likely cause. This likely aetiology has again been suggested in a recent paper, a response to a critique of the bundle, where the authors again state that ‘the rise in OASI is more likely to be due to better recognition’. As well as making the initiating reasons for the Care Bundle quite unclear, the authors in several papers continue to speculate as to the cause of the ‘increase’ in SPTs (or increase in detection).

Reasons given for the suggested increase include:

- training inconsistencies, lack of awareness and variation in practice

- inconsistencies in practice with regards to hands on or hands poised

- increasing use of a hands-poised approach to protecting the perineum during childbirth as opposed to a hands-on approach

It is interesting that an increase in the hands poised approach (as opposed to hands on) is suggested as a reason for the possible increase in rates, while a recent systematic review demonstrated that a hands on technique resulted in a similar incidence of SPT compared to a hands poised technique. The authors also found that a hands-on approach increased the incidence of third-degree tears and need for episiotomy. This was supported by another recent paper by Australian colleagues.

Furthermore, a Cochrane review failed to come to any conclusion regarding the use of hands on or poised, but did find that hands poised technique may reduce episiotomy. The review also found that the use of warm compresses may reduce the rate of 3rd and 4th degree tears. The beneficial effect of warm packs was found to be even stronger in a recent meta-analysis we published.

It is unclear therefore where the assertion that the ‘increased rate’ of SPTs may be due to increased use of the hands poised technique comes from. The authors of the trial say that in 2014 a systematic review of intrapartum interventions to reduce SPT was apparently carried out, by RCOG, RCM and others, and this forms the apparent evidence base of the Care Bundle. However, this appears to have never been published.

How can the evidence base for an intervention clearly intended to be rolled out nationally not be published or made available to the public?

“The care bundle was presented to a group of influential RCM members committed to midwifery practice around labour and birth” (RCM/RCOG, 2019)

Apparently, the results of the review, which included ‘over 2000 studies’ were made available to the OASI Care Bundle Group, including representatives from the RCM. Yet the RCM, in their 2018 Blue Top Guidelines for midwifery care in labour state that that there is no evidence that having a hands poised approach has any effect on the rate of third and fourth degree tears, but may result in fewer women requiring episiotomy. They also say that ‘there is insufficient evidence to show whether Ritgen’s manoeuvre or other perineal techniques could improve outcomes, but that there is good evidence that using a warm compress on the perineum, and some evidence that perineal massage during birth may help to reduce the rates of third and fourth degree tears’.

As far as we can tell the literature review was not published and we can’t find it on the Care Bundle webpages. Here they present only two pieces of evidence. One is the original study (which concluded the that the increase in rates were probably due to increased recognition), and the other is an RCOG document which highlights inconsistencies in the rates of many maternity care practices across English NHS Trusts, including (for primiparous women):

- Induction of labour (ranging between 16.3% and 43.1%)

- Instrumental births (from 13.1% to 41.8%)

- episiotomy (from 16.2% to 50.8%)

- episiotomy with an instrumental birth (39.3% to 98.5%, for both multips and primips)

- 3rd and 4th degree tears (from 2.0% to 9.3%)

The developers of the Care Bundle do not seem to have considered how they might reduce variation in practices such as induction of labour or instrumental birth, but instead focus on the hands on/hands poised debate, a practice not assessed in any of the evidence presented here. While a recent CQC survey found that 44% of women who responded experienced induced labour and 37% of women gave birth in the lithotomy position, it is unclear why the RCM and others have not chosen to address these modifiable factors, before thinking of adding another intervention to the mix. Indeed the RCM, in a response letter to the ARM’s expressed concerns about the Care Bundle, say they have ‘been aware (for at least the past eight years) of an increasing tendency for midwife attended births to take place in lithotomy, contrary to enhancing physiological birth’; making it perhaps more confusing that they do not choose to address this issue.

Indeed, in the original paper that appears to have instigated development of this Care Bundle, the authors are clear that instrumental births are a key determinant of the risk of tears. It is surprising therefore that the variation in instrumental births was not addressed in any strategic attempt to reduce the incidence of SPTs.

“Mode of delivery is a key determinant of the risk of perineal tears, with studies consistently demonstrating that women with instrumental deliveries have higher rates of anal sphincter tears. The risk of having a severe perineal injury has been reported to be 1.5–14.0 times higher with forceps, and up to four times higher with ventouse, than with spontaneous vaginal delivery” (original paper)

The ‘evidence-based’ Care Bundle

The Care Bundle is based on the premise that a set of EVIDENCE-BASED interventions, when used together, result in better outcomes than if the interventions were performed alone. However, this is based on the assumption that each of the elements is based on the best evidence available.

There are four elements of the Care Bundle, none of which appear to be based on strong evidence and all of which evoke many questions:

1) Antenatal information for women about SPTs and what can be done to minimise risk

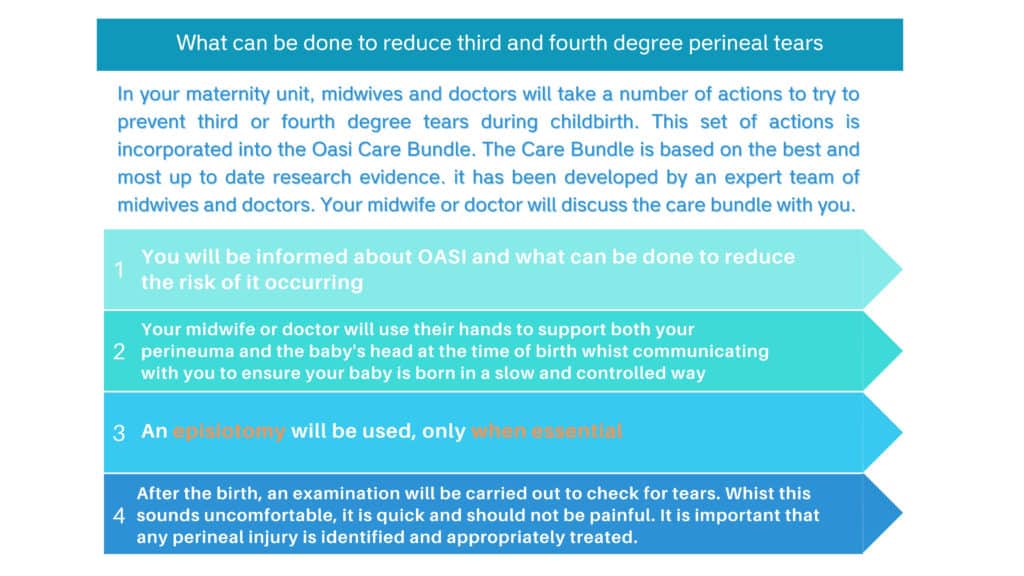

- According to the information leaflet (see below), what can be done to minimise risk is the Care Bundle, which is not evidence based.

- It is unclear how telling women that the bundle will reduce their risk of SPT is an evidence-based intervention to reduce the risk of SPT, though we absolutely support informing women antenatally about what may reduce perineal trauma.

- It is also unclear whether as part of this discussion, midwives are able to discuss the at best ‘patchy’ evidence to support manual perineal protection and that there is evidence to show that it can increase the risk of tearing for multiparous women, and that it may increase the risk of episiotomy.

The authors say that ‘great care was taken not to affect in any way women’s choices regarding their care’ – how can this be the case when midwives are to comply through telling women that the Care Bundle will reduce their risk of tearing? Of course this will impact on their choices. It is not the provision of information however that is the problem, as inferred in the recent qualitative evaluation of the Care Bundle, where the authors state that, ‘some clinicians do not fully understand the balance between discussing risk and maintaining women’s autonomy’. It is that in order to balance risk and maintain autonomy, the information given should be evidence based.

2) Documented use of manual perineal protection (MPP):

- For spontaneous births, MPP should be used, unless the women objects.

- For operative vaginal births, MPP should always be used (not clear what will happen if she ‘objects’).

- In response to a critique of the lack of an evidence base for the use of MPP, the authors of the trial agree that the evidence is indeed ‘patchy’, but argue that ‘no evidence of an effect’ does not equate to ‘evidence of no effect’. It is at this point we enter a world of alternative facts where virtually anything you believe can be argued contrary to what the evidence says,

- While possibly true at a stretch, it does not equate to an evidence-based intervention to reduce the risk of SPT. Furthermore, it is hardly a sound basis on which to base an intervention to be rolled out nationally costing no doubt substantial amounts of money, though there is no data we can find on this.

We agree that a number of recent systematic reviews demonstrate that the evidence of the effectiveness of the hands-on approach for OASI is patchy. However, ‘no evidence of an effect’ does not equate to ‘evidence of no effect’ (Thaker et al, 2020)

3) When indicated, episiotomy should be performed mediolaterally at a 60-degree angle at crowning.

- For women, this element of the Care Bundle is presented as, ‘an episiotomy will be used, only when essential (highlighted, as if it might otherwise be carried out when not absolutely essential); what is not made clear to women, is that it is actually a change in the angle of the episiotomy that makes up this component of the Care Bundle.

- However, in itself, a change in the angle of episiotomy does not appear to be a high level evidence-based method to reduce the risk of SPT.

- It is unclear whether this may in fact be a means through which to gain consent for episiotomy (should it be required) antenatally, thus protecting against potential litigation.

4) Following birth, the perineum should be examined, and any tears graded according to the RCOG guidance. The per rectum examination should be done even when the perineum remains intact.

- This element is not about reducing the risk of tearing, it is aimed at detecting tears. Therefore, it is unclear how a post birth per-rectum check will reduce the risk of tearing.

- How often tears occur where the woman’s perineum is intact and what practitioners are to do about it if one is detected is another matter that appears to have been over-looked, but is information that we should surely be able to provide woman in order to gain informed consent for an intervention that will likely impact on the immediate post-birth experience, despite the fact that it may be ‘quick and should not be painful’. Of major concern here is women who may have experienced sexual abuse potentially being retraumatised, especially where informed consent is not in place.

While the only evidence-based practice that is recommended in the RCM Blue Top guidance is the use of warm compresses, it is unclear why this evidence-based intervention would not be recommended as part of any bundle aimed at reducing SPTs. It is claimed that this was because ‘the clinical practicalities of ensuring standardisation made it unfeasible to include as a component of the care bundle’. With all the complex technology and medications health providers navigate it is mystifying as to why a warm cloth on a woman’s perineum is considered to be so complex. One could also argue that it is impossible to achieve standardisation of antenatal discussions, MPP, episiotomy and PR examination technique – to detect something that seems to have been very rarely detected.

Perhaps we need to think about what sort of knowledge is valued in maternity care, where a bundle of non-evidence-based interventions is accepted into practice, because a group of experts say it is evidence based; all the while, an aspect of care that doesn’t fit with the medical model is excluded based on the fact that it can’t be standardised, or is simply not believed as it is not considered technical enough.

Yet, through implementation and evaluation of the Care Bundle, warm compresses were apparently ‘encouraged as part of intrapartum care’, and so could have impacted on outcomes (as the only evidence-based intervention considered, it seems more likely that they might have). However, the use of warm compresses was unaccounted for in the evaluation.

‘Each Care Bundle element is applied to every patient, every time’

While midwifery is supposedly based on a foundation of individualised, evidence-based care and autonomous decision making, it is unclear how this fits when you demand mandatory compliance with a non-evidence based intervention aimed at standardising care. Where is the individual woman in all of this?

It is unclear why the RCM are supporting and advocating for this bundle or how a quality improvement project can be based on interventions not proven to improve quality. It is also unclear why the OASI committee failed to consider other practices, such as lithotomy and instrumental birth, known to be highly variable between Trusts, and instead chose to speculate that an increase in the hands poised approach may be the cause. It seems that dominant medical discourses around birth and women’s bodies are considered more convincing than actual evidence. It appears that the only answer to ‘wicked problems’ in modern day obstetrics must always lie in increasing intervention, rather than looking at what we are doing to women during birth that might be leading to poor outcomes.

Recent systematic reviews in 2018 and 2020 on homebirth show a halving in SPT for low risk women birthing at home compared to obstetric units. The great irony is most women giving birth at home do so in water, are upright and have minimal perineal interference. Perhaps it is our medicalised models of care that are the bigger reason behind a rise in SPT, but this conversation challenges power and belief and so is always dismissed.

Is this Care Bundle part of a re-negotiating of the boundaries of midwifery practice? Perhaps the only way midwives are likely to be taken seriously in the medical model is by walking the technocratic path? That the RCM has chosen to sign up to this approach continues to perplex many midwifery leaders. Will the art of midwifery at the time of birth as a result be lost to compliance and standardisation?

If the ‘QI project was designed with the implementation strategy given as much consideration as the intervention itself’, it is no wonder so much work had to go into it, with the lack of any convincing evidence base. As a result of this drive to increase ‘buy-in’, the project often comes across as marketing, as if, if everyone is enthusiastic enough we will all forget about the fact that nearly everything about the Care Bundle is completely unconvincing.

We will be interested to read the study into women’s experiences (due Autumn 2020).

FUTURE STEPS

There are questions that remain that need to be addressed:

- Will the change in the SPT rate be sustained?

- Does the decreasing background rate account for the decrease seen in this study?

- Were there other undocumented and perhaps unnoticed contributors to this change?

- The intervention with perhaps the best evidence for reducing SPT (warm compresses) was excluded from the main recommendations with claims it would be too hard to standardise. While warm compresses were apparently ‘encouraged as part of intrapartum care’, we have no idea how often they were used and this could have impacted on final outcomes. Perhaps the reduction in SPT would have been even greater had they been included.

- Level 1 evidence does not support benefit from routine hands on the perineum during the birth.

- The impact on women of the Care Bundle still needs to be fully evaluated, including impact on birth positions and women’s psychological trauma.

- Will we see the episiotomy rate increase eventually

- Why was the Care Bundle not based on the best available evidence when this is the central tenet of Bundles? Why also was the evidence base for the Care Bundle not published when this was undertaken? Is it possible that it did not support the elements that were preferred?

Professors Jim Thorton and Hannah Dahlen published a paper this year calling for the two Colleges (RCM and RCOG) to convene a new Care Bundle group to consider the evidence and produce a revised bundle. We suggested the following:

Where to next?

- Women should be informed and prepared for birth and hence given antenatal information about SPT and its prevention.

- Midwives and doctors should protect the perineum by slowing the birth of the baby with whatever technique they feel most appropriate. Hands on and hands poised are both acceptable along with verbal guidance. Specific manoeuvres such as head flexion, the C-Grip, Ritgen’s manoeuvre and the Finnish grip are not recommended due to insufficient evidence of benefit.

- Perineal warm compresses are Level 1 evidence and should be offered to all women

- Episiotomy should only be performed where indicated. Routine episiotomy is not recommended. Midline episiotomy is not recommended, but both 45 degree and 60 degree medio-lateral episiotomy are acceptable until higher level evidence is available.

- For women with an episiotomy or a perineal tear, a digital rectal examination is recommended and discussed with women to exclude both anal sphincter injury and button-hole tears. For women in whom careful inspection of the perineal and lower vaginal skin reveals no tear, a digital rectal examination is not necessary. Consent must always be sought. (Thornton & Dahlen, 2020).

While the results of the study may be in there is little doubt the jury is still out on this issue and no doubt there will be more publications, debates and alternatives suggested for years to come. In the meantime, are we practising according to the best available evidence, or are we complying with the pull of the technocratic approach despite the absence of any convincing evidence?

Gill Moncrieff @GillMoncrieff

Hannah Dahlen @HannahDahlen

Feature image credit: Brendan Doyle

Nicky Leap

This critique is SO useful and much needed. Thank you both.

Nicky Leap