Covid-19 and Maternal and Infant Health: Are We Getting the Balance Right? A Rapid Scoping Review

Anastasia Topalidou, Gill Thomson, Soo Downe – THRIVE Centre, Faculty of Health and Wellbeing, University of Central Lancashire, UK

Published in The Practising Midwife, Volume 23 Issue 7 July/August 2020 https://doi.org/10.55975/ZYUT2405

Aim: The purpose of this study was to summarise the evidence of the clinical and psychological impacts of COVID-19 on perinatal women and their infants.

Methods: A rapid scoping review was conducted based on methods proposed by Arksey and O’Malley, and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) practical guide for rapid reviews. We searched EMBASE, MEDLINE(R) and MIDIRS.

Results: From 1,319 hits, 26 met the inclusion criteria and were included. Most of the studies (n=22) were from China. The majority of the publications are single case studies or case reports. The findings were analysed narratively, and six broad themes emerged. These were: Vertical transmission and transmission during birth, mother-baby separation, breastmilk, likelihood of infection and clinical picture, analgesia or anaesthesia, and infants and young children. The literature search revealed that there is very little formal evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on pregnant, labouring and postnatal women, or their babies. The clinical evidence to date suggests that pregnant and childbearing women, and their babies, are not at increased risk of either getting infected, or of having severe symptoms or consequences, when compared to the population as a whole, which contrasts with outcomes for this group in other viral pandemics. There is no evidence on the short- and longer-term psychological impacts on childbearing women during COVID-19.

Conclusion: Despite this lack of evidence, many maternity services have been imposing severe restrictions on aspects of maternity care previously acknowledged as vital to optimum health (including birth companionship, breastfeeding, and contact between mother and baby). There is a critical research gap relating to the clinical and psychological consequences of both COVID-19 and of maternity service responses to the pandemic.

Background

Being pregnant and/or having a baby is, ideally, an event that is associated with joy, delight, and fulfilment, following a safe and positive pregnancy, birth, and early parenthood. However, some women can experience negative emotions during this period, including anxiety and depression. Being pregnant and giving birth during a pandemic can not only bring clinical risks to mother and baby, but also psychological stress. Some of the practices enacted by maternity services in the name of reducing infection risk for mother, child, or staff, could exacerbate these risks. For example, during the current COVID-19 outbreak there have been reports of women being unable to be accompanied by a birth companion during labour, routine use of caesarean section, denial of the right to breastfeed, and routine separation of birthing people from their babies,1-3 with potential harmful impacts for mothers and infants, including ‘toxic stress’4 and perceptions of self-blame and shame.5

Globally, the extent and adverse impacts of maternal mental health problems are increasingly recognised. As the World Health Organization (WHO) states “virtually all women can develop mental disorders during pregnancy and in the first year after delivery”. Conditions such as extreme stress, emergency and conflict situations and natural disasters can increase risks for specific mental health disorders.6 Apart from the overall population-level pandemic-related stress, there is limited formal evidence-base about the nature and clinical consequences of epidemics for a pregnant woman.7 There are no insights into the impacts of restricted choices on women’s birth and parenting behaviours, highlighted above. There is even less information about the mental health impacts consequent to self-isolation, living in a household with an affected person, limited access to goods/services and to routine or emergency health and social care. For women (and especially for those living in poverty, in poor or cramped housing), these issues may be exacerbated if they are expected to be the main carers for elderly or infirm relatives, or for young children, while living with multiple family members in confined spaces. As maternal mental health problems are associated with longer-term risks for the mother, partner, and children,8-11 this raises the question: how are we safeguarding the short- and longer-term mental health of pregnant women and their partners in the age of coronavirus?

The most recent WHO guidelines for antenatal and for intrapartum care reinforce the importance of positive clinical and psychosocial pregnancy and childbirth experiences to optimise the physical and psychosocial wellbeing of mother, baby, and the family in the short and longer term.12,13 In order to ensure that the current rapid restructuring of maternity services to cope with the pandemic can take account of all the relevant consequences, we undertook a rapid scoping review to assess the clinical and psychological impacts of COVID-19 on pregnant women, new mothers and infants.

Methods

A scoping review was considered the most appropriate method to approach the broad aim of this study, as it is more flexible than standard meta-analytic systematic review which aims to answer specific questions. A scoping review has been described as a process of producing a broad overview of the area of interest.14-15 Rapid reviews are recognised as an optimal approach for health systems to produce contextualised knowledge to aid decision-making.16 The protocol for the current rapid scoping review was structured using the scoping review methodological framework described by Arksey and O’Malley,15 and the WHO’s practical guide for rapid reviews.16

Search strategy

An extensive literature search to identify studies published from the earliest date in each database until 3 April 2020 was conducted. One author (AT) performed a search of the following databases: Embase (1974 to 2020 April 03), Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily (1946 to April 03, 2020) and Maternity & Infant Care Database (MIDIRS) (1971 to February 2020). The search was designed to retrieve all articles combining the concepts of: (((pregnancy or pregnant or maternal or antenatal or prenatal or intrapartum or perinatal or postnatal or postpartum or birth or childbirth or delivery or baby or infant or newborn) and COVID-19) or SARS-CoV-2 or HCoV-19). The search strategy included studies in any language. Based on the practical guide for rapid review,16 the above sources and databases were considered by the researchers as the most suitable for the objective of the study.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We did not assess the methodological quality of the included studies in this scoping review, as the purpose was to scan the literature and to determine what has been reported so far. We included all records reporting cases or any clinical or psychological data related to: women who received antenatal, perinatal and postnatal care and were positive to COVID-19; pregnant, childbearing or puerperal women or new mothers who were positive to COVID-19; and infants, newborns and babies who either are positive to COVID-19 or have a mother positive to COVID-19. Reviews or records that did not report new or original data were excluded.

Screening and charting

The screening and the charting were performed by one reviewer (AT). At the first stage, the titles and abstracts of articles identified by the search strategy were screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. Studies meeting the criteria outlined were charted using Microsoft Excel and the full texts were assessed for final inclusion. The bibliographic reference lists of all articles to be included were checked to identify any additional eligible publication.

Analysis

A narrative synthesis was undertaken, drawing on the guidance by Popay et al.17 This approach was selected as the findings were not suitable for meta-analysis, and as the intention was to adopt a ‘storytelling approach’ (p5); to describe the evidence of the impacts of COVID-19 on the health and wellbeing of parents and infants. A translational analytical approach was undertaken.17 This involved a) a summary of the main findings from each of the included studies was detailed; b) the summaries were mapped and organised under key themes, on an iterative basis; c) the summaries included within each theme were explored to identify similarities and differences; d) three professional associations/organisations, WHO, UNICEF, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) were searched for guidelines and/or recommendations related to the reported findings/themes. AT led on data analysis, and the final themes were agreed by all authors.

Results

A total of n=1319 records that were identified via the databases and screened by title and abstract. Nighty-eight records were taken forward for full text review. After the final full text selection, n=26 records remained and were included. No further records that fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were identified by checking the reference lists of the included papers. The screening process and final included studies are reported in the flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow chart of literature review process

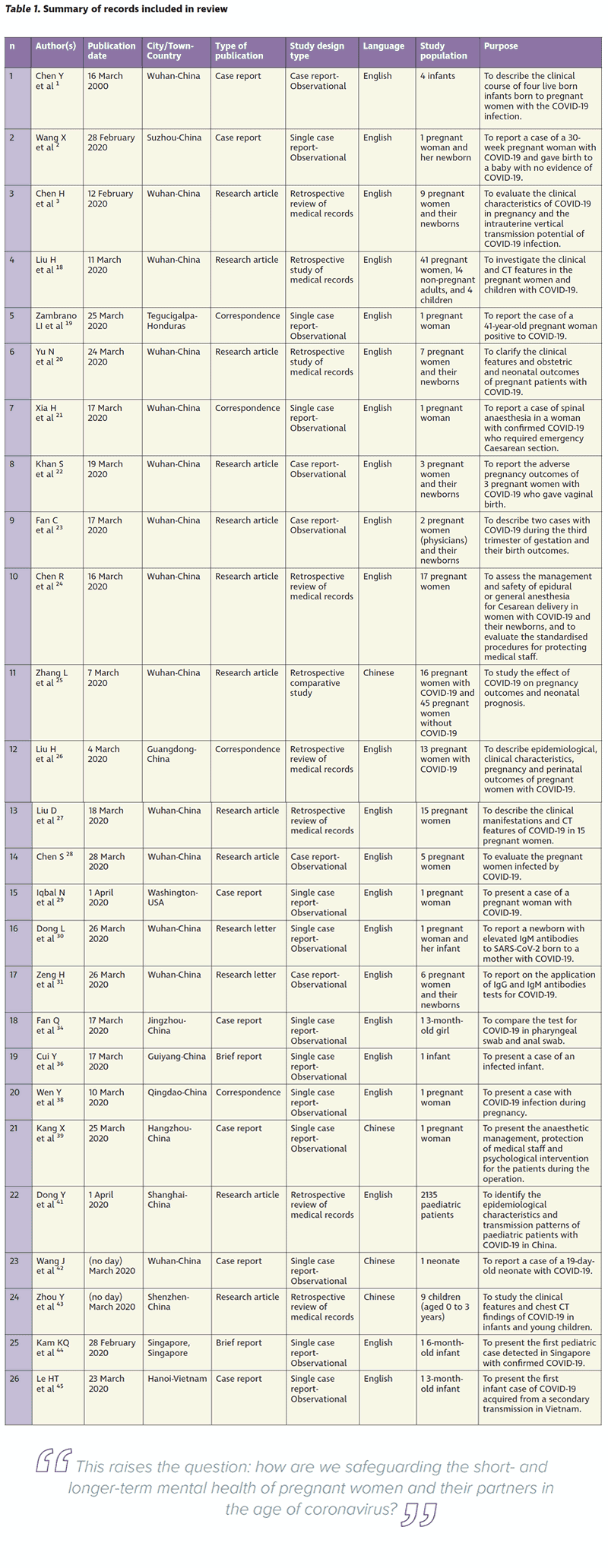

The characteristics of the n=26 included records are presented in Table 1. Twenty-two papers were written in English and n=4 in Chinese. All the papers were published during the period 12th February – 1st April 2020 with n=4 of them being published on the 17th March. The included studies were undertaken in the following countries: Honduras (n=1), USA (n=1), Singapore (n=1), Vietnam (n=1) and China (n=22). Out of the n=22 papers from China, n=14 were from Wuhan where the outbreak emerged.

From the n=26 included records, n=9 were retrospective studies. The remaining n=17 studies were case reports, with n=12 being single case reports. In total, 112 cases of pregnant women and 29 cases of women with their newborns are presented. In addition, nine cases of infants who were either infected with COVID-19 or were born to mothers who were positive to COVID-19, are described. In a separate study that included four children only, two of them were below one year of age (two months and 11 months).18 Finally, in a large paediatric study that reported 2,135 cases, children were reported as being <18 years of age, with 379 cases being <one year of age.

The findings are described below.

Clinical findings

The narrative analysis generated six broad themes: vertical transmission and transmission during birth, mother-baby separation, breastmilk, likelihood of infection and clinical picture, analgesia or anaesthesia, and infants and young children.

a) Vertical transmission and transmission during birth:

There is no definitive evidence that the virus can be transmitted vertically from the mother to the fetus during pregnancy.2,3,18-26 No virus was detected in the maternal serum, amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal nasopharyngeal swab, vaginal swab, umbilical cord blood, placenta tissue and breastmilk samples.3,23

There is no reported transmission during birth. Infants born vaginally or by caesarean section, to mothers with coronavirus infection, have so far been shown to be negative to COVID-19.1,2,20,22,24-29

A recently reported single case of a neonate that tested positive for COVID-19 does not provide definitive evidence of intrauterine or intrapartum infection, as no intrauterine tissue sample was tested, and the neonate was tested (throat swab) 36 hours after birth. The neonate had mild shortness of breath, but no fever or cough and was discharged after two weeks.3,20 There is another single case report where a neonate born to a mother with COVID-19 had elevated antibody levels and abnormal cytokine test results two hours after birth. The elevated IgM (Immunoglobulin M) antibody level suggests that the neonate could be infected in utero: although infection at delivery cannot be ruled out.30 In another study with six infected mothers, COVID-19 was not detected in the serum or throat swab in any of their newborns. However, virus-specific antibodies were detected in neonatal blood sera samples.31 In the last two cases30,31 where the evidence of transmission was based on elevated IgM and IgG (Immunoglobulin G) antibody values, “no infant specimen had a positive reverse transcriptasepolymerase chain reaction test result, so there is not virologic evidence for congenital infection in these cases to support the serologic suggestion of in utero transmission”.32

WHO states that “We still do not know if a pregnant woman with COVID-19 can pass the virus to her foetus or baby during pregnancy or delivery. To date, the virus has not been found in samples of amniotic fluid or breastmilk”.33

b) Mother-baby separation:

Despite the above single case of a neonate that was confirmed to be positive to COVID-19,20 the risk/benefit calculation is that mothers and babies should not be routinely separated after birth to prevent transmission of COVID-19. In four published studies, infants were isolated from their mothers immediately after birth for up to 14 days.1,2,29,34 However, the guidelines from WHO for mothers infected with COVID-19 are “close contact and early, exclusive breastfeeding helps a baby to thrive”, “hold your newborn skin-to-skin” and “share a room with your baby”.33 In addition, UNICEF’s recommendations during the period of the outbreak are “regardless of feeding method, it is essential that sick and preterm babies’ profound need for emotional attachment with their parents/primary caregiver continues to be considered. Keeping mothers and babies together wherever possible and responding to the baby’s need for love and comfort will not only enable breastmilk/breastfeeding, but will also protect the baby’s short- and long-term health, wellbeing and development. In addition, this will support the mother’s mental wellbeing in the postnatal period”.35

c) Breastmilk:

There is no evidence or biological indication that COVID-19 can be transmitted through breastmilk.2,28,36 As the benefits of breastfeeding are well known, particularly in terms of boosting the infant’s immune system, and maternal and child bonding, WHO recommends that “women with COVID-19 can breastfeed if they wish to do so”. Given the potential for postnatal transmission indicated by the single confirmed case of neonatal infection noted above, WHO adds that women who are breastfeeding, and, indeed, those who are giving babies formula milk, should “practice respiratory hygiene during feeding, wearing a mask where available, wash hands before and after touching the baby and routinely clean and disinfect surfaces they have touched”.33

d) Likelihood of infections and clinical picture:

There is no evidence to date that pregnant women are more likely to acquire COVID-19 than other young adults, or that, once they have it they have more severe disease, or that those with mild or severe disease have a higher risk of fetal distress or of adverse fetal outcomes.21,23-27,37 The WHO reports “At present there is no evidence that they are at higher risk of severe illness than the general population. However, due to changes in their bodies and immune systems, we know that pregnant women can be badly affected by some respiratory infections. It is therefore important that they take precautions to protect themselves against COVID-19, and report possible symptoms”.33

e) Analgesia or anaesthesia:

There is no evidence that epidural, spinal or general anaesthesia is contraindicated.2,21,24,38 The RCOG reports that as general anaesthetic can exacerbate spread of the virus, epidurals should be provided early to women with suspected or actual symptoms. “There is no evidence that epidural or spinal analgesia or anaesthesia is contraindicated in the presence of coronaviruses. Epidural analgesia should therefore be recommended before, or early in labour, to women with suspected/confirmed COVID-19 to minimise the need for general anaesthesia if urgent delivery is needed, and because there is a risk that use of Entonox may increase aerosolisation and spread of the virus”.39

f) Infants and young children:

In one large observational study of 2,143 paediatric patients with COVID-19 in China, although the overall incidence of severe disease was highest in the under one-year-old group (10.6%), this was still much lower than in adult patients (18.5%). This suggests that babies and children are much less at risk of adverse effects of being infected with COVID-19, and much less likely to die as a result than adults.40 Infants and young children with COVID-19 tend to have mild clinical symptoms.41,42 There are four reported cases of secondary transmission from parents or family members to infants. One infant was 55 days old, two were three months old and one was six months old.34,36,43,44 Based on RCOG guidance “children, including newborns, do not appear to be at high risk of becoming seriously unwell with the virus”.39

Psychological findings

No studies were found for COVID-19 relating to maternal mental health. Only one study mentioned that special attention and support should be given to maternal psychology, but this was in relation to anaesthesia management during caesarean section. This study did not investigate maternal mental health, but described the psychological support that should be provided to women before and during the operation. This included explaining the procedure to reduce anxiety, relief of the discomfort during the operation to reduce tension etc.

Discussion

This rapid scoping review provides an overview of current evidence relating to COVID-19 and maternal and neonatal health. Study selection and data abstraction conducted by one reviewer is acceptable for rapid reviews due to time constraints.16 Pre-print databases were not searched as their included records have not been evaluated or certified by a peer review process, and therefore cannot be used to guide practice or for knowledge synthesis.

The majority of the included studies were from China (84.6%). Apart from two single case reports, one from the USA and one from Honduras, the current knowledge is based on studies from Asia. While on 13 March Europe became the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic, with more cases than the rest of the world combined (apart from China), there are no published studies yet from any European country. As the guidelines and the healthcare practice differ between countries, we do not know yet the real impact of the COVID-19 outbreak either on the pregnant women who are affected or all pregnant women and their babies. For instance, guidelines from China suggest that “infants should not be fed with the breast milk from mothers with confirmed or suspected of 2019-nCoV” and suspected cases mother or infants should be isolated and separated.45 Same guidelines suggest that “delayed cord clamping (DCC) is not recommended” and that “mother-baby contact is also not recommended”.45

Current evidence suggests that pregnant women and babies are no more at risk of catching COVID-19 than other members of the public. There is no evidence that pregnant women are more likely to experience severe illness than other young adults, or that even severe illness due to COVID-19 is more likely to be associated with adverse neonatal outcomes (when compared to other severe maternal illness). While there are a very few cases in which maternal to infant transmission may have occurred in utero, this evidence is not definitive. This body of knowledge is based on case reports and observational studies, with most of them having small cohorts and consequent limitation.

There is recent anecdotal evidence of policies in which maternity-related staff restrict maternal choices and rights (such as routine induction of labour, separation of mother and baby) in the name of protection of mother and/or baby; these practices are not justified based on current evidence, and are likely to be associated with physical and psychological harm. Recommendations not to breastfeed should be actively avoided. These practices are also occurring despite authorities including the WHO, the International Confederation of Midwives, the RCOG, and the Royal College of Midwives, all issuing guidance clearly stating that these practices must be avoided during COVID-19.

There are no studies for COVID-19 relating to maternal mental health, and to the best of our knowledge there are no studies or case reports that explored the influence of other epidemics or pandemics such as H1N1 influenza or 2014-16 Ebola on the mental health of expectant, or new mothers. The lack of evidence on psychological health is a critical gap. It is especially important when two of the Millennium Development Goals (4 and 5) emphasise maternal and child health, stating that overall health cannot be achieved without mental health.8

Table 1. Summary of records including in review

Psychosocial stress, particularly during early pregnancy, has been identified as a key risk factor in the aetiology of a preterm birth.46 The potential (ill-informed) practices of restricted maternal choices and behaviours will undoubtedly exacerbate maternal co-morbidities.47-48 Furthermore, while the links between social isolation and depression are well reported,49 negative impacts are likely magnified when coupled with juggling the demands of confined family members. A recent article titled “The Coronavirus Is a Disaster for Feminism” also highlights how women’s independence is the ‘silent victim’ of the pandemic due to women being more likely than males to take responsibility for caregiving activities.50 This situation is even more acute for women who face complex life issues such as poverty, or domestic violence. Women may be exposed to an increased risk of domestic violence, or who are trying to protect children from risks of abuse from relatives who are now confined at home; with a 300% increase in domestic violence cases reported in China during the pandemic.51 Recent headlines also report further impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on women’s choices, such as Texas banning abortions as a nonessential operation – with little consideration of the mental fallout and wider implications of this decision-making.52

Even though there is plenty of scientific evidence and experience-based knowledge in several fields from the previous two coronaviruses, the research on MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV and pregnancy/childbirth is still limited, for clinical outcomes, and especially in terms of maternal mental health. There are therefore critically important gaps in our knowledge about how pandemics affect mothers and their babies, and how pregnant women, mothers and their families can be better supported. In February 2020, several reports were published in The Lancet stating that mental healthcare should be included in the national public health emergency systems and that further understanding was needed to better respond to future unexpected disease outbreaks.53-57 Prenatal and postnatal physical health and mental health must be prioritised to optimise short- and long-term impacts on maternal, familial and fetus, infant and child biopsychosocial development.58

Conclusion

The information provided in the results of this rapid review may change as knowledge evolves on a daily basis. The clinical findings and the presented results can support the emerging need to adapt policies and strengthen the health systems. However, more data from more countries and regions are needed to support the evidence-informed policymaking globally. The lack of knowledge about the short- and longer term psychological wellbeing of mother and baby following their experiences of maternity care during a pandemic is a serious gap in knowledge. In the absence of formal evidence, the potential for adverse mental health consequences of the pandemic should be recognised as a critical public health concern, together with the need to identify how to prevent and ameliorate any negative impacts. TPM

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and material

All articles retrieved through standard university searches. All data used are presented and included within the manuscript.

Competing interests

GT is an Associate Editor of the BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. AT and SD declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding for this study.

Authors’ contributions

AT, GT, SD conceived of the review, coordinated the review process and wrote the first draft. AT conducted the search, the selection of the records for inclusion, and extracted the data. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This paper relates to the EU COST Action CA18211: DEVoTION: Perinatal Mental Health and Birth-Related Trauma: Maximising best practice and optimal outcomes.

References

- Chen Y, Peng H, Wang L, Zhao Y, Lingking Z, Hui G et al. Infants born to mothers with a new coronavirus (COVID-19). Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2020;8:104.

- Wang X, Zhou Z, Zhang J, Zhu F, Tang Y, Shen X. A case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in a pregnant woman with preterm delivery. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020.

- Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, Luo F, Yu X, Zhang W, et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. The Lancet. 2020;395(10226):809-815.

- Shonkoff J, Garner A, The Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependence Care, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Siegel B.S, et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 012;129(1):e232-246.

- Thomson G, Ebisch-Burton K, Flacking R. Shame if you do-shame if you don’t:women’s experiences of infant feeding. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(1):33-46.

- World Health Organization. Mental Health-Maternal Mental Health. https://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/maternal_mental_health/en/. Published 2020.Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Schwartz D. An Analysis of 38 Pregnant Women with COVID-19, Their Newborn Infants, and Maternal-Fetal Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Maternal Coronavirus Infections and Pregnancy Outcomes. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2020.

- Alipour Z, Kheirabadi G, Kazemi A, Fooladi M. The most important risk factors affecting mental health during pregnancy: a systematic review. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24(6):549-559.

- Patel V, Rahman A, Jacob K, Hugnes M. Effect of maternal mental health on infant growth in low income countries: new evidence from South Asia. BMJ. 2004;328(7443):820-823.

- Stein S, Pearson R, Goodman S, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M, et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. The Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1800-1819.

- Bauer A, Parsonage M, Knapp M, Iemmi V, Adelaja B. Costs of perinatal mental health problems. Centre for Mental Health and London School of Economics, London. https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-09/costsofperinatal.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed March 21, 2020.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/anc-positive-pregnancy-experience/en/. Published 2014. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/intrapartum-care-guidelines/en/. Published 2018. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- Armstrong R, Hall B, Doyle J, Waters E. Scoping the scope’ of a cochrane review. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33(1):147-150.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32.

- World Health Organization. WHO Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/publications/rapid-review-guide/en/. Published 2017. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden AJ et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic Reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Lancaster: Lancaster University; 2006.

- Liu H, Liu F, Li J, Zhang T, Wang D, Lan W. Clinical and CT Imaging Features of the COVID-19 Pneumonia: Focus on Pregnant Women and Children. The Journal of Infection. 2020.

- Zambrano L, Fuentes-Barahona I, Bejarano-Torres D, et al. A pregnant woman with COVID-19 in Central America. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;101639.

- Yu N, Kang Q, Xiong Z, Wang S, Lin X, Liu Y, et al. Clinical features and obstetric and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective, single-centre, descriptive study. The Lancet. 2020;20(5):559-564.

- Xia H, Zhao S, Wu Z, Luo H, Zhou C, Chen X. Emergency Caesarean delivery in a patient with confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 under spinal anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124(5):e216-e218.

- Khan S, Peng L, Siddique R, Nabi G, Nawsherwan, Xue M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 infection on pregnancy outcomes and the risk of maternal-to-neonatal intrapartum transmission of COVID-19 during natural birth. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 2020:1-9.

- Fan C, Lei D, Fang C, Li C, Wang M, Liu Y, et al. Perinatal Transmission of COVID-19 Associated SARS-CoV-2: Should We Worry?. Clin Infect Dis. 2020.

- Chen R, Zhang Y, Huang L, Cheng B, Xia Z, Meng Q. Safety and efficacy of different anesthetic regimens for parturients with COVID-19 undergoing Cesarean delivery: a case series of 17 patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020 Jun;67(6):655-663.

- Zhang L, Jiang Y, Wei M, Cheng B, Zhou X, Li J, et al. Analysis of the pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19 in Hubei Province. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2020;55(0):E009.

- Liu Y, Chen H, Tang K, Guo Y. Clinical manifestations and outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy. J Infect. 2020.

- Liu D, Li L, Wu X, Zheng D, Wang J, Yang L et al. Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes of Women With Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pneumonia: A Preliminary Analysis. AJR American Journal of Roentgenology. 2020; 1-6. 10.2214/AJR.20.23072.

- Chen S, Liao E, Shao Y. Clinical analysis of pregnant women with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2020;10.1002/jmv.25789.

- Iqbal S, Overcash R, Makhtari N, Saeed H, Gold S, Auguste T, et al. An Uncomplicated Delivery in a Patient with COVID-19 in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(16):e34.

- Dong L, Tian J, He S, et al. Possible Vertical Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 From an Infected Mother to Her Newborn. JAMA. 2020;;323(18):1846-1848.

- Zeng H, Xu C, Fan J, et al,. “Antibodies in Infants Born to Mothers With COVID-19 Pneumonia”. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1848-1849.

- Kimberlin D, Stagno S. Can SARS-CoV-2 Infection Be Acquired In Utero?: More Definitive Evidence Is Needed. JAMA. 2020.

- World Health Organization. Q&A on COVID-19, pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding. https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-on-COVID-19-pregnancychildbirth-and-breastfeeding. Published 2020. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Fan Q, Pan Y, Wu Q, Liu S, Song X, Xie Z, et al. Anal swab findings in an infant with COVID-19. Pediart Invest. 2020;4(1):48-50.

- UNICEF The baby friendly initiative. Infant feeding on neonatal units during the COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/infant-feeding-onneonatal-units-during-the-COVID-19-outbreak/?fbclid=IwAR1JlZr93mWEPbo2GNLW7lMFQCn7so25mlIycpwYp7lojLXLFc6Cu1mtfYk. Published 2020. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Cui Y, Tian M, Huang D, Wang X, Huang Y, Fan L, et al. A 55-Day-Old Female Infant infected with Covid 19: presenting with pneumonia, liver injury, and heart damage. J Infect Dis. 2020;221(11):1775-1781.

- Wen R, Sun Y, Xing Q. A patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy in Qingdao, China. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020.

- Kang X, Zhang R, He H, Yao Y, Zheng Y, Wen X. et al. Anesthesia management in cesarean section for a patient with coronavirus disease 2019. Zhejiang da xue xue bao. Yi xue ban. 2020:49(1):0.

- Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection in Pregnancy: Information for healthcare professionals. https://www.rcm.org.uk/media/3780/coronavirus-COVID-19-virus-infection-in-pregnancy-2020-03-09.pdf. Published 2020. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, Qi X, Jiang Z, Tong S. Epidemiological characteristics of 2143 pediatric patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in China. Pediatrics. 2020.

- Wang J, Wang D, Chen G, Tao X, Zeng L. SARS-CoV-2 infection with gastrointestinal symptoms as the first manifestation in a neonate. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi.2020:22(3):211-214.

- Zhou Y, Yang G, Feng K, Huang H, Yum Y, Mou X, et al. Clinical features and chest CT findings of coronavirus disease 2019 in infants and young children. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;22(3):215-220.

- Kam K, Yung C, Cui L, Lin Tzet Pin R, Mak T, et al. A Well Infant with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) with High Viral Load. Clin Enfect Dis, 2020.

- Le H, Nguyen L, Tran D, Do H, Tran H, Le Y, et al. The first infant case of COVID-19 acquired from a secondary transmission in Vietnam. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(5):405-406.

- Wang L, Shi Y, Xiao T, Fu J, Feng X, Mu D, et al. Chinese expert consensus on the perinatal and neonatal management for the prevention and control of the 2019 novel coronavirus infection. 1st ed. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(3):47.

- Shapiro G, Fraser W, Frasch M, Seguin J. Psychosocial stress in pregnancy and preterm birth: associations and mechanisms. Journal of perinatal medicine. 2013;41(6):631-645.

- DiMatteo R, Morton S, Lepper H, Damush T, Carney F, Pearson M, et al. Cesarean childbirth and psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 1996;15(4):303-314.

- Borra C, Iacovou M, Sevilla A. New evidence on breastfeeding and postpartum depression: the importance of understanding women’s intentions. Maternal and child health journal. 2015;19(4):897-907.

- Matthews T, Danese A, Wertz J, Odgers C, Ambler A, Moffitt T, et al. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: a behavioural genetic analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:339-348.

- Lewis H. The Coronavirus Is a Disaster for Feminism. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/03/feminism-womens-rights-coronaviruscovid19/608302/. Published 2020. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- Feng J. COVID-19 Fuels Domestic Violence In China. SUPCHINA. 2020. https://supchina.com/2020/03/24/COVID-19-fuels-domestic-violence-in-china/. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- MailOnline. Texas governor bans most abortions during coronavirus outbreak because they ‘don’t qualify as essential surgeries’ – as Ohio considers following suit. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8147325/Texas-moves-ban-abortionscoronavirus-outbreak.html. Published 2020. Accessed 24 March 2020.

- Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng S, Shi J, Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower society. The Lancet. 2020;395(10224):PE37-E38.

- Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, Guo J, Fei D, Wang L, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet. 2020;7(4):PE15-E16.

- Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang B, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. The Lancet. 2020;7(3):14.

- Duan L, Zhu G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. The Lancet. 2020;7(4):300-302.

- Yang Y, Li W, Zhang Q, Zhang L, Cheung T, Xiang Y. Mental health services for older adults in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet. 2020;7(4):PE19.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal and postnatal mental health. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs115/resources/antenatal-and-postnatalmental-health-pdf-75545299789765. Published 2016. Accessed March 21, 2020.