Inequalities AND Unreasonable Adjustments: Are D/deaf women being given a detrimental care pathway in the name of risk assessment?

Rachel Crowe – Second-year midwifery student, Bournemouth University and Yeovil District Hospital

Published in The Practising Midwife Volume 23 Issue 8 September 2020 https://doi.org/10.55975/YVIZ2811

Summary

In the UK, pregnant women who are hearing impaired or D/deaf (sign language users) and deaf (who are hard of hearing but who have English as their first language and may lipread and/or use hearing aids) are often labelled as high risk and offered a care pathway that is unsuitable and detrimental to their care. Identifying the gaps in maternity that exist in current guidelines and practice can help midwives to ensure women get appropriate, high-quality woman-centred care. This article provides an overview to the needs of D/deaf birthing people with a number of recommendations and tools for use in clinical practice.

Background

Definitive statistics for the number of D/deaf women accessing maternity care are hard to find but in 2016, the Office for National Statistics1 reported there were approximately 61,800 people of childbearing age living in the UK whose main health concern was hearing loss. D/deaf awareness is therefore vital for all of us in the maternity profession, even though the number of women we encounter each year may be small. D/deaf women face many challenges such as: lack of appropriate communication or reasonable adjustments,2 lack of appropriate time for consultations,3 poor attitudes of staff and a lack of D/deaf awareness.4 Misperception of D/deafness by healthcare professionals was identified as a common experience for D/deaf women, which engendered or re-confirmed a sense of isolation – in particular, assumptions about English as a preferred language.5 Signhealth6 illustrate the ways in which the NHS system creates barriers for D/deaf people, relying on auditory methods to arrange appointments and failing to provide interpreters.

Adjustments for communication

It is understood that D/deaf people access English in a similar way to someone for whom it is their second language.7 It is common for D/deaf children to experience a delayed response to language and an increased dependence on visual cues for communication.8 However, the aetiology of D/deafness is extensive and varied, therefore an individualised needs assessment is important. There are two main challenges this creates: one of language and a more subtle one of literacy comprehension. Therefore, D/deaf people need reasonable adjustments9 in order to communicate with their maternity team effectively10 – this could mean British Sign Language (BSL) or Sign Supported English (SSE) through an interpreter.

D/deafness and maternity guidelines

Many D/deaf people consider their D/deafness a normal part of life rather than a disability and themselves to be part of a unique, linguistic-culture minority group.11 However, many D/deaf women find their pregnancies labelled high risk due to D/deafness. This appears to be because of lack of training and D/deaf awareness among staff.12 Further research is needed to determine the real attitudes of staff, as the occurrences in the current research are self-reported and it was not the focus of the research. The NICE guidelines have no clear maternity care pathway for D/deaf women, which could be confusing for staff. Section 1.3 of guideline CG110 applies to some D/deaf women,10 and yet appears to be focused on ethnicity. D/deafness itself is not a medical condition needing obstetric intervention,13 however, D/deaf women are at higher risk of developing mental health problems, of which practitioners need to be aware.14

Solutions

-

Considering the accessibility issues to postnatal discharge videos led me to ask the matron at Yeovil District Hospital (YDH) if I could facilitate a BSL interpreter into the filming of postnatal hospital discharge videos. The videos will be available on the YDH website (creation and release of these videos has been delayed by COVID-19 and will be accessible in due course) and through their use, ensure women who communicate through BSL get the information in their first language.

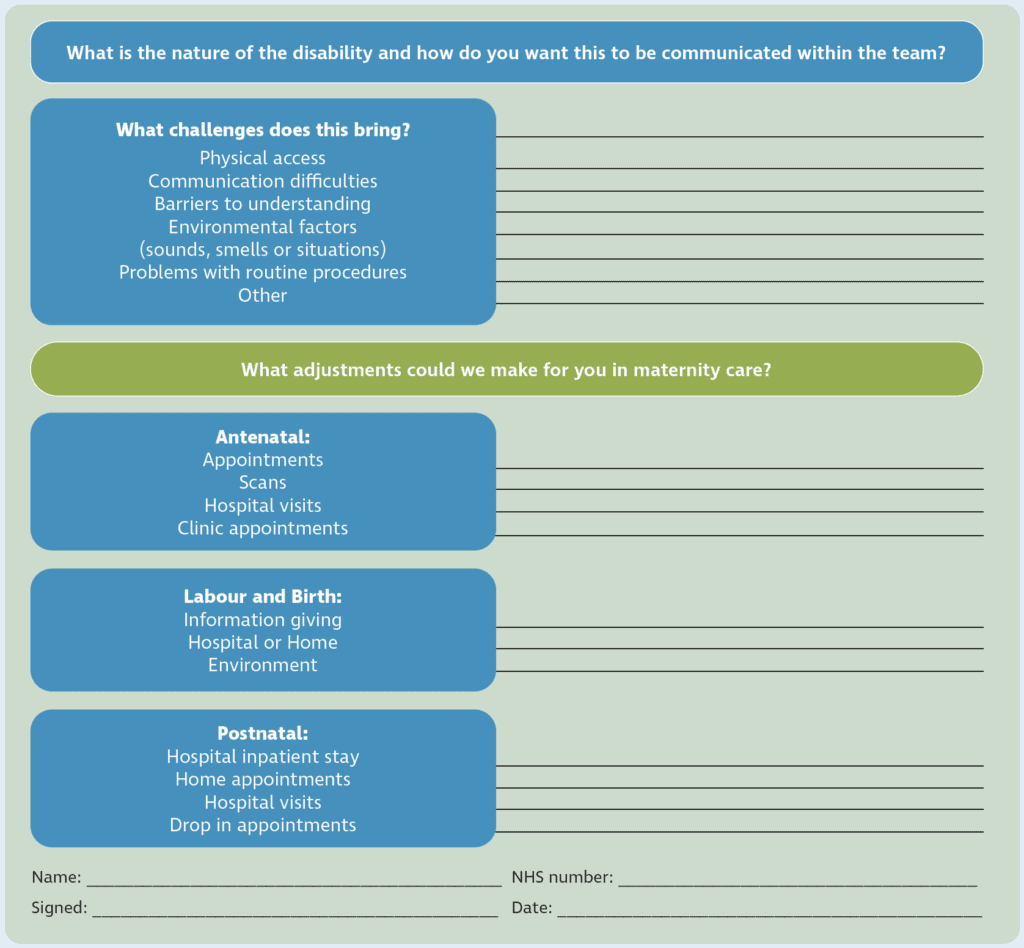

- To facilitate the booking appointment, I developed the following resource (see Figure 1), which can be used with women with any disability to decide a woman-centred care plan.

- To facilitate care pathway decision-making, I developed a flow chart to help midwives (see Figure 2).

- To facilitate ongoing communication with D/deaf women and for their labour needs should they birth in a hospital or birth centre, I have created a list of top tips to guide maternity professionals (see Figure 3). Be aware that the woman may have a long relationship with the audiology department, which can be involved in facilitating this.

Conclusion

Many midwives will have a reasonable amount of D/deaf awareness, but even this may not be enough for a woman to access the most appropriate pathway of care, especially where there is a lack of clarity from national guidelines. Empowering midwives to make considered decisions with D/deaf women can facilitate the best care pathway for the woman. The ability to show this clinical judgement, partnered with women’s own preferences, safeguards the midwife by demonstrating the process in the documentation. This should begin to disassemble the inequalities that D/deaf women face and lead to better outcomes and a better experience of maternity services for them and their families. TPM

Figure 1: Booking resource (downloadable PDF button further down page)

Equalities and Reasonable Adjustments

Part 1: This tool is for you and your midwife to discuss. It’s to help us know you better and be able to decide what pathway of care would be most suitable for you. Don’t worry if you’re not sure what you need, this is designed to help you start the discussion – it’s not a final decision and can change with you!

Figure 2: Flow chart for care planning (downloadable PDF button further down page)

This is a guide to help your midwife decide who might need to be involved in your care and how we make that as accessible for you as possible.

Reasonable adjustments are modifications that will overcome challenges caused by disability, e.g. physical aids, changes to policy, assistance, translators, extra time etc.

Figure 3: Resources for consistent communication (downloadable PDF button further down page)

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Janet Thomas (BSL and lipreading teacher) and Stella Rawnson (University lecturer at BU) for your support in my research and writing.

References

- Difficulty in hearing and the Annual Population Survey. Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/aboutus/transparencyandgovernance/freedomofinformationfoi/difficultyinhearing

andtheannualpopulationsurvey. Published 19 February, 2018. Accessed March 26, 2020. - Walsh-Gallagher D, McConkey R, Sinclair M, Clarke R. Normalising birth for women with a disability: The challenges facing practitioners. Midwifery. 2013;29(4):294-299.

- Malouf R, Henderson J, Redshaw M. Access and quality of maternity care for disabled women during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period in England: data from a national survey. BMJ. 2017;7(7):e016757.

- Lawler D, Begley C, Lalor J. (Re)constructing myself: the process of transition to motherhood for women with a disability. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2015;71(7):1672-1683.

- Parsons J. Deafness, pregnancy and sexual health. The Practising Midwife. 2014;17(4):12-14.

- Sick of it. How the health service is failing deaf people. The Deaf Health Charity. Signhealth. https://signhealth.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Sick-Of-It-Report.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 19, 2020.

- Deuchar M, James H. English as the second language of the deaf. Language & Communication. 1985;5(1):45-51.

- Scott J, Dostal H. Language development and deaf/hard of hearing children. Education Sciences. 2019;9(2):135.

- Equality Act 2010. Legislation.gov.uk. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents. Updated 26 June 2020.

- Pregnancy and complex social factors: a model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors. Clinical guideline CG110. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg110/chapter/1-Guidance. Published September 22, 2010. Accessed May 19, 2020.

- Marschark M, Zettler I, Dammeyer J. Social dominance orientation, language orientation and deaf identity. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2017;22(3):269-277.

- Sporek P. The deaf nest project. A report into deaf and hard of hearing people’s experiences of maternity care. Deaf nest. https://b4b72140-ebb4-4d31-9f7a-a025d84f2143.filesusr.com/ugd/ddfcd5_94e2a9c779a846cc8e6bd495d6b52d68.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 19, 2020.

- Antenatal care for uncomplicated pregnancies. Appendix C: Women requiring additional care. Clinical Guidance CG62. NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg62/chapter/Appendix-C-Women-requiring-additional-care. Updated February 4, 2019. Accessed May 19, 2020.

- Jackson M. Deafness and antenatal care: Understanding issues with access. British Journal of Midwifery. 2011;19(5):280-285.

- Deaf awareness. Action On Hearing Loss. https://beta.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/information-and-support/deaf-awareness/. Published 2020. Accessed May 19, 2020.