Infant Feeding: Changing the Conversation

Francesca Entwistle – Midwife and Professional Advisor (Policy and Advocacy) to the Unicef UK Baby Friendly Initiative

Published in The Practising Midwife Volume 21 Issue 9 October 2018

Summary

Francesca Entwistle, Midwife, RCM member and professional advisor to the Unicef UK Baby Friendly Initiative, explains how the Royal College of Midwives’ (RCM) recent position statement on infant feeding and the media response (RCM 2018) lays blame incorrectly on individual midwives, while ignoring the real issues at stake: the vulnerability of breastfeeding in the UK and the lack of real choice for many mothers who want to breastfeed but find this impossible (Unicef UK 2016). She discusses the importance of addressing the reasons behind the UK’s low breastfeeding rates, and of taking action across healthcare, government and society settings to enable mothers to breastfeed for as long as they wish.

It was predictable that the RCM’s position statement on infant feeding and accompanying press release (RCM 2018) would be followed by negative publicity, but the extent of the vitriol in the media the next day was shocking. ‘End of breastfeeding tyranny’ screamed the Daily Mail front page (Borland 2018a) – just one of many articles implying that midwives were currently bullying mothers into breastfeeding and that the RCM had at long last told them to stop (Borland 2018b). Midwives and infant feeding leads across the UK were hugely disappointed. How could the organisation that represents them imply that they and their entire profession were failing women?

The RCM states that the main update to their position statement is an emphasis on respecting mothers’ choices. Of course women’s choices should be respected. But this statement misses some important facts.

Respecting choice

Firstly, the great majority of midwives do respect women’s infant feeding choices. Against a backdrop of significant time constraints and a lack of resources, midwives strive to have sensitive, mother-centred conversations around infant feeding (Unicef UK 2018a); the vast majority of midwives are extremely sensitive to the need to respect individual decisions around this most contentious of issues. Indeed, the last three Care Quality Commission (CQC) surveys reported significant improvements in care, with more women reporting that midwives respected their infant feeding choices and provided relevant and consistent infant feeding advice.

Importantly, only 3.5 per cent of mothers said their decisions about how they wanted to feed their baby were not respected by midwives (CQC 2017).

A real choice to breastfeed

Secondly, women in the UK often do not have a real choice to breastfeed, with eight out of 10 mothers reporting having stopped breastfeeding before they wanted to and only 10 per cent of mothers reporting that they met their breastfeeding goals (NHS England 2016; McAndrew et al 2012). Evidence shows that when mothers are offered ongoing, predictable, face-to-face support from people who believe they can do it and believe that breastfeeding is important, they are much more likely to achieve their infant feeding goals and feel satisfied with their care (McFadden et al 2017).

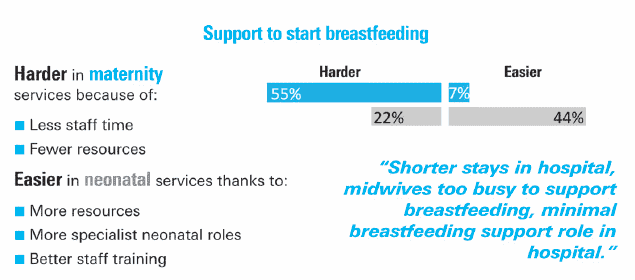

But in the UK the ability to provide this much-needed support is being undermined. In 2017, Unicef UK published findings from a survey of infant feeding leads in England, showing that many services are being cut and that this is impacting the level of support that mothers and babies receive (Unicef UK 2017a). Similarly, research from Cardiff University highlights that many women in the UK do not receive the peer support they need to enable them to continue to breastfeed (Anonymous 2018). This year, Unicef UK asked health professionals about how changes to services were affecting their ability to implement the Baby Friendly standards in England. The results show significant variation between standards, across maternity, community and neonatal services, and across different regions. These pressures on support provision make it much more difficult for mothers to breastfeed for as long as they wish.

These cuts to support are particularly worrying in the UK because we live in a culture where breastfeeding is not the norm. From very early childhood, a toy bottle is given to little girls to feed their dolls. When these little girls become mothers, many won’t even have seen a breastfeed, let alone feel confident to do it themselves. And when mothers do initiate breastfeeding and there are concerns that the baby isn’t feeding enough, is feeding too much, doesn’t settle, doesn’t sleep through the night, or when a mother wants to go out in public, or go back to work or for a hundred other reasons, the answer – from family, friends, the media and, crucially, from formula milk advertising, is always, always to bottle feed (Ashmore 2018). In this culture, support from health professionals to breastfeed is particularly vital, and without it our breastfeeding rates will continue to plummet, making breastfeeding seem even less achievable and ‘normal’.

And why is the protection of this support so important? The truth we must face is that human milk and breastfeeding are the physiological norm for feeding and responding to babies’ needs, unique to each infant; this cannot be replicated, and the UK’s low breastfeeding rates have profound implications for infant and maternal health.

Championing support for all families

Gill Walton states that “some women for a variety of reasons struggle to start or sustain breastfeeding.” But this doesn’t mean we should stop promoting breastfeeding – we have a duty to address the reasons behind the struggle – a lack of individual and societal support for breastfeeding mothers. In the UK so many mothers (including many who are midwives) have not breastfed, or have experienced the trauma of trying very hard to breastfeed and not succeeding, leaving a legacy of pain that closes down conversations and leads to a reluctance to even raise the issue. There must be kindness, support and informed, empowered choice for those who don’t breastfeed or whose breastfeeding journey ends before they are ready. The Unicef UK Baby Friendly Initiative, for example, works to raise the standards of care that all families receive, including the provision of evidence-based information, free from commercial interest, for families who formula feed, supporting them to do so as safely and responsively as possible (Unicef UK 2018c).

We must absolutely respect the right to informed choice, but we must acknowledge that without the right support – from society, policy makers, healthcare services and a culture which normalises breastfeeding – many mothers have no choice but to stop breastfeeding. We must not let down future generations by shying away from championing a mother’s right to breastfeed, if that is her wish. We must look to successes elsewhere – from Scotland to Norway – and learn from others’ strategic approaches to improving breastfeeding rates (Unicef UK 2018d; Ashmore 2018).

We know that a successful breastfeeding relationship brings so much joy to mother and baby and sets both up for a healthy, happy life, and so many mothers want this for themselves and their baby, but are denied the support to make it happen. The RCM should be using its privileged position to campaign for equality of services across the UK.

We know that a successful breastfeeding relationship brings so much joy to mother and baby and sets both up for a healthy, happy life, and so many mothers want this for themselves and their baby, but are denied the support to make it happen. The RCM should be using its privileged position to campaign for equality of services across the UK.

The RCM’s statement, in failing to fully acknowledge the realities of infant feeding in the UK, is leaving those working at the forefront exposed. Midwives are subject to the same societal barriers and criticism as anyone else and need support from the RCM to stand up against the UK’s huge societal and commercial pressures that undermine breastfeeding and promote the use of breast-milk substitutes. Without a united voice for all those who speak up for mothers’ and babies’ rights, we undermine midwives’ crucial work to support happy, loving, breastfeeding relationships between mothers and babies.

The RCM talks about facing up to reality. However, their statement feels like it has missed the causes of our current reality and, in so doing, risks blaming rather than supporting midwives in this difficult work. TPM

Key pointsEight out of 10 women stop breastfeeding before they want to. We have a duty to address the reasons behind why women in the UK struggle to breastfeed, and provide individual and societal support for them to continue. It is time to stop laying the blame for this major public health issue in the laps of individual women and midwives, and acknowledge the collective responsibility of all to change the conversation, from blame to support. Unicef UK urges UK governments to implement four key actions and to create a supportive, enabling environment for women who want to breastfeed. Find out more: http://unicef.uk/bficalltoaction |

References

- Anonymous (2018). ‘’Despairingly lacking’: a midwife on support for breastfeeding mothers’. The Guardian, 27th July. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/jul/27/despairingly-lacking-midwife-support-breastfeeding-mothers

- Ashmore S (2018). Relieving the feeding pressure, London: Unicef UK. https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/relieving-the-feeding-pressure/

- Borland S (2018a). ‘End of breast feeding tyranny’. Daily Mail, 12th June. https://www.pressreader.com/uk/daily-mail/20180612/281479277118037

- Borland S (2018b). ‘End of breastfeeding shaming’. Mail Online, 12th June http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5832733/Midwives-ordered-not-judge-new-mothers-choose-bottle-feed.html

- CQC (2017). Maternity services survey 2017, London: CQC. https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/surveys/maternity-services-survey-2017

- McAndrew F, Thompson J, Fellows L et al (2012). Infant Feeding Survey 2010, Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/infant-feeding-survey/infant-feeding-survey-uk-2010

- McFadden A, Gavine A, Renfrew MJ (2017). ‘Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies’. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2: CD001141. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub5.

- NHS England (2016). National maternity review. Better births. Improving the outcomes of maternity services in England. A five year forward view for maternity care, London: NHS England. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/national-maternity-review-report.pdf

- RCM (2018). Position statement on infant feeding, London: RCM. https://www.rcm.org.uk/news-views-and-analysis/news/rcm-publishes-new-position-statement-on-infant-feeding

- Unicef UK (2016). Call to action campaign, London: Unicef UK. http://unicef.uk/bficalltoaction

- Unicef UK (2017a). The state of support services for mums and babies, London: Unicef UK. https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/the-state-of-infant-feeding-support-services/

- Unicef UK (2017b). Cuts that cost, London: Unicef UK. https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/cuts-that-cost/

- Unicef UK (2018a). Guidance for antenatal and postnatal conversations, London: Unicef UK. https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/baby-friendly-resources/implementing-standards-resources/guidance-for-antenatal-and-postnatal-conversations/

- Unicef UK (2018b). Spotlight on infant feeding care in England, London: Unicef UK. https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/spotlight-on-infant-feeding-care-in-england/

- Unicef UK (2018c). Infant formula and responsive bottle feeding: a guide for parents, London: Unicef UK. https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/baby-friendly-resources/bottle-feeding-resources/infant-formula-responsive-bottle-feeding-guide-for-parents/

- Unicef UK (2018d). More women in Scotland are breastfeeding their babies at six months, London: Unicef UK https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/more-women-in-scotland-breastfeeding/

- Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD et al (2016). ‘Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect’. The Lancet, 387(10017): 475-490.