Birth on Film

Laura Godfrey Issacs – Artist, Birth Activist and Midwife at King’s College London

When I was working as a student midwife a woman I was looking after, who had a BBA (born before arrival) or unplanned home birth, noted that she did not think herself in established labour – as, in the birth programmes she watched the women were screaming so much, which was not matching her own experience, that she ended up having the baby unexpectedly at home, after which she commented – ‘it wasn’t that bad!’.

Lesley Page, former President of the RCM, writing in her editorial ‘Birth in the Bright Lights’ (2013) suggests how she would like to see modern birth as ‘not just a scene in a hospital labour ward…(but) the start of life and the family’. Sheila Kitzinger (2001) also wrote about how birth is portrayed on film; the sudden onset of labour, the inevitable rush to hospital, followed by screams, pain and a medicalised birth which, she suggested, normalise and encourage women to ‘submit’ to this potential scenario.

However, independent, campaigning films and those produced by women themselves via YouTube and social media, often challenge dominate media narratives about birth and present women’s subjective experiences, hidden voices and bodily autonomy – which, I would suggest, is where we and women preparing for birth should be looking for images of childbirth – not to Hollywood or mainstream media.

The History of Birth on Film

Whilst, in the first part of the twentieth century pregnancy and birth was only suggested in film, not explicitly named – for example in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), by Tennessee Williams, directed by Elia Kazan and starring Vivien Leigh and Marlon Brando, in the second half of the century it appeared in all genres of film.

Many themes have emerged in mainstream films such as pregnancy horror – epitomised by Rosemary’s Baby (1968) with Mia Farrow, directed by Roman Polanski, and then later in sci-fi such as Aliens (1979) directed by Ridley Scott. Another familiar genre is, The Momcom (or pregnancy romcom) such as ‘The Back up Plan’ (2010), ‘Knocked up’ (2007) and ‘Baby on Board’ (2009). It is widely thought that Demi Moore’s naked pregnant photo ‘More on Moore’ by Annie Leibowitz for Vanity Fair (1991) initiated a time where pregnancy was connected with ‘glamour and desirability’ (Hanson, 2004) and ushered in a whole new genre of pregnancy Romcom films.

Similarly, the first birth was only shown on British TV in 1957, variously described as ‘revolting’ and ‘tasteless’, whereas content analysis of American soap operas as far back as 1988 represented eight times the national pregnancy average, and BBC portrayals in 1993 showed a birth every four days (Clements, 1997). Fast forward to 2018 and we are used to numerous television programmes such as Call the Midwife (BBC 1, 2014) and One Born Every Minute (Channel 4, 2015), and a proliferation of images and portrayals on the internet and social media, from ‘YouTube births’ and documentaries, to campaigns and commercial projects, with birth seemingly ubiquitous on film.

Analysis of birth on film

This can also be seen in many mainstream film representations, where the narrative often elevates the obstetric discourse and implies that women should fear birth and expect to be assisted with medical intervention, and that ‘natural’ childbirth is an unrealistic expectation. Further to this it could be argued that narratives tend to promote dominant societal constructs around femininity and the ‘good’ woman and in extension the ‘good’ obstetric patient.

‘Understanding the content of these depictions is critical because women’s attitudes and behaviour during pregnancy and birth are guided by gendered norms of expression, which are often taken from institutions such as the media’ (Morris & McInerney, 2010)

The Male Gaze

Ways of Seeing, the seminal book by art critic John Berger (1972), critiqued how women are objectified and the subject of the male gaze in art. This concept was further developed by Laura Mulvey (1975) for narrative film, which reveals how women are framed by the dominant male gaze, and appear as characters who usually play highly controlled parts in a story (Boswell, 2014). The film industry is woeful in promoting female directors with only 7% in the top 250 grossing American films in 2014 (The Guardian, 2015), and, it is noted, the more producers and censors are involved, the more control is exerted over the female characters (Boswell, 2014). With the recent revelations through the #metoo campaign, it is clear that women have had their power in the film industry seriously compromised.

Other issues around the representation of pregnancy and birth in film suggests how our fascination may be traced to how these bodies deviate from the norm (the male body) and how ‘the female subject has to negotiate the monstrous, the inconsistent and the anomalous’ (Battersby, 1998).

Feminist scholars such as Camilla. A Sears and Rebecca Godderis () in their analysis of birth in reality TV in America, suggest these shows use ‘personal history as spectacle’ and ‘lifestyle surveillance’ to both dramatise birth as well as seek to control women’s bodies. They also noted the reinforcement of social norms, through predominantly portraying Caucasian, married, heterosexual, able-bodied and economically secure women with little diversity. Further, medicalization of birth is reinforced as the norm, with the predominant hospital setting and non-problematicised medical interventions as an essential part of the birth experience.

A challenge to the norm?

Similarly, documentaries around birth like, The Business of Being Born (2008) by American actress Rikki Lake and filmmaker Abby Epstein, explore birth in the context of the US system of healthcare, and Birth Time (2018) currently in production in Australia seeks to address the failures of maternity services, such as rising medical interventions and specific issues for indigenous women ‘birthing on country’. Whereas, films such as The Premier Cri by Gilles de Maistre (2008) explore birth in a more anthropological context.

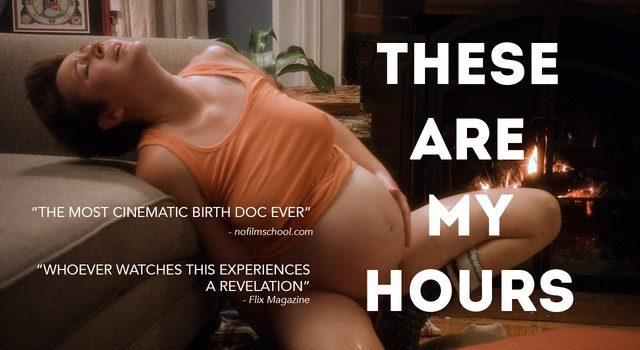

The recently released These are my Hours (2018) by American doula and director Scott Kirschenbaum provides a direct and visceral experience of one woman’s labour at home – powerfully exploring the physical and psycho-social aspects of birth and asserting a woman’s autonomy over her body.

And a film yet to be made, ‘Mother may I?’ by Cristen Pascucci, hopes to deal with birth trauma and obstetric violence.

Another alternative form are the many short films freely available on the internet that address health issues and research that often use animation, illustration and graphics. These films use social marketing methods, and creative strategies to promote public health messages and research and are highly effective at engaging a wide audience. Examples of those connected with birth and reproductive health include ‘Amina’s Story’ (2016) by The Service– about sex trafficking in Tanzania, ‘My Mum’s Got a Dodgy Brain’ (2016) by ForMed Films about maternal mental health, respectful maternity care by The White Ribbon Alliance (2018), #findthewords (2018) about pregnancy loss by charity Sands and ‘Milk for Tiny Humans’ (2018) about breastfeeding.

Equally some powerful creative films have been produced by performance poet Hollie McNish (2016) with director Jake Dipla, based on her poems such as ‘Embarrassed’ about breastfeeding in public.

With these contrasting pictures of dominant narratives, that tend to dramatise, generate fear and promote medicalisation as the norm, alongside a growing body of films that unpack such narratives with individualised and politicised positions, how can midwives positively engage with birth on film and support women to do so too.

A midwife’s response

- Watch documentaries such as Vicki Elson’s ‘Laboring Under an Illusion’ (2009) which gives a comprehensive look at birth on film, or read ‘Knock me up, Knock me down – images of pregnancy in Hollywood films by Oliver (2012) which fleshes out most of the major themes.

- Ask women at the first contact, the booking appointment, or at antenatal classes what their experience is of birth on film, in order to work to address fears, hopes and questions which might be generated partly by this plethora of images and messages.

- Become ‘media savvy’ and help decode edited, often over-dramatic representations of birth.

- Encourage women themselves to be more ‘media literate’ to unpack the birth clichés or myths

- Get involved in redressing the balance to create more realistic and positive images of labour and birth, as suggested by Denis Walsh in his Birth write piece ‘Childbirth according to Hollywood’ (2007) – create your own blog, short films or advise producers and directors who are working on films or TV that include birth.

References

Amina’s story (2014) The Service https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xYCHdKIF4kM&feature=youtu.be

Baby on Board (2009) Lucky Monkey Picture https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baby_on_Board_(film)

Battersby C (1998) The Phenomenal Woman: Feminist Metaphysics and Patterns of Identity. Routledge, New York.

BBC 1 (2018) Call the Midwife. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0118t80

Berger J (1972) Ways of Seeing. Penguin, UK

Birth Time (2018) https://www.birthtime.world

Boswell P A (2014) Pregnancy in Literature and Film. McFarland & Company, North Carolina

The Back up Plan (2010) CBS films. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Back-up_Plan

Butcher G (2014) Fearful birth? So what’s new? The Practising Midwife. Vol 17. No.4. 19-21

Brodrick A (2014) Too afraid to push: dealing with fear of childbirth. The Practising Midwife. Vol.17. No.3 15-17

Brodrick A (2014) The Fear Factor – why are primigravid women fearful of birth? MIDIRS Midwifery Digest 24:3:327-332

Clement S (1997) Childbirth on Television, British Journal of Midwifery, Jan 1997, Vol.5. No.1

Channel 4 (2018). One Born Every Minute. Available online at: http://www.channel4.com/programmes/one-born-every-minute.

Find the Words (2018) Sands https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wPovVrRSRlY&feature=youtu.be

Garrod D (2012) Birth as Entertainment, British Journal of Midwifery, February 2012, Vol.29. No.2

The Guardian (2015) Number of female directors falls over last two decades

Available online at: http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/jan/13/number-of-female-film-directors-falls-over-last-two-decades

Elson V & Conway M A (2009) Laboring Under an Illusion: Mass Media Childbirth vs. the Real Thing (DVD). Available online at: http://www.birthmedia.com/

Hanson C (2004) A Cultural History of Pregnancy: Pregnancy, Medicine and Culture 1750-2000. Palgrave MacMillan, New York

Hundley V, Duff E, Dewberry J, Luce A, van Teijlingen E (2014) Fear in childbirth: are the media responsible? MIDIRS Midwifery Digest 24:4:444-447.

Juno (2007) Fox Searchlight Pictures https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juno_(film)

Kitzinger S & Kitzinger J (2001) Sheila Kitzinger’s and Jenny Kitzinger’s Letter from Europe: Childbirth and Breastfeeding in the British Media. Birth – issues in perinatal care. Available online at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/1523536x/2001/28/1

Kirschenbaum K (2018) These are My Hours. Available online at: https://thesearemyhours.com

Knocked Up (2007) Universal Pictures. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knocked_Up

Lake R & Epstein A (2008) The Business of Being Born: available online at: http://www.thebusinessofbeingborn.com/

Liebovitz A (1991) More on Moore, Vanity Fair. Available online at: http://100photos.time.com/photos/annie-leibovitz-demi-moore

McNish H & Dypka J (2016) Embarrassed https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S6nHrqIFTj8

Oliver K (2012) Knock me up, Knock me down: Images of Pregnancy in Hollywood Films. Columbia University Press/New York

Le Premier Cri (2007) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hzzSVRK_m6s

Milk for Tiny Humans (2018) http://www.human-milk.com

Morris T & McInerney K (2010) Media Representations of Pregnancy and Childbirth: An Analysis of Reality Television Programs in the United States. Birth. Vol.37. No.2 p134-140

Mulvey L & Rose R (1975) Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Afterall Books: Two Works

My Mum’s Got a Dodgy Brain (2016) Formed Films https://vimeo.com/151633908

Page L (2013) Birth in the Bright Lights, British Journal of Midwifery, April 2013, Vol.21. No.4

Polanski R (1968) Rosemary’s Baby. Paramount Pictures https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosemary%27s_Baby_%28film%29

Precious (2007) Lionsgate https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Precious_(film)

Sears C A & Godderis R (2011) Roar Like a Tiger on TV?,

Feminist Media Studies, 11:2, 181-195

These are my Hours (2018) https://vimeo.com/ondemand/thesearemyhours

(Discount Code to download the whole film: BABYCATCHER)

Young D (2010) Childbirth Education, the Internet, and Reality Television: Challenges Ahead. Birth – Issues in Perinatal Care. 37-2

Walsh D (2007) Childbirth according to Hollywood, British Journal of Midwifery, November 2007, Vol.15, No.11

White Ribbon Alliance (2018) Available online at: https://www.whiteribbonalliance.org/films